Your cart is currently empty!

Duplicity in Foreign Policy: The Shifting Narrative of ISIS and the Jihadist Flag

The United States’ foreign policy often exemplifies a strategic duplicity, particularly in its handling of groups like ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria). This relationship, which oscillates between condemnation and tacit alignment, reveals an unsettling flexibility in defining “good” and “bad” actors based on immediate geopolitical needs. In recent years, this duplicity has manifested starkly in Syria, where U.S. interests have sometimes aligned with ISIS fighters against a common enemy, highlighting a deeply pragmatic, if morally ambiguous, approach.

The Case in Syria: Enemies Turned “Allies”

In Syria, the narrative around ISIS has shifted subtly but significantly. Once the ultimate enemy, representing terror and extremism, ISIS fighters recently took out targets deemed “bad” by U.S. foreign policy. Specifically, ISIS actions against Syrian leaders or factions unfavorable to U.S. interests have prompted less condemnation and, at times, quiet approval. This evolving dynamic suggests that the U.S. is willing to temporarily overlook its historic enmity with ISIS if their actions align with broader strategic objectives in the region.

This strategic hypocrisy is not new. The U.S. has a long history of “enemy-of-my-enemy” tactics, supporting groups that later become adversaries. Afghanistan in the 1980s offers a clear parallel, where U.S. support for the Mujahideen ultimately facilitated the rise of groups like the Taliban and al-Qaeda. The cyclical nature of these alliances underscores the lack of long-term vision in U.S. foreign policy, where today’s allies can easily become tomorrow’s existential threats.

The Flag as a Symbol of Complexity

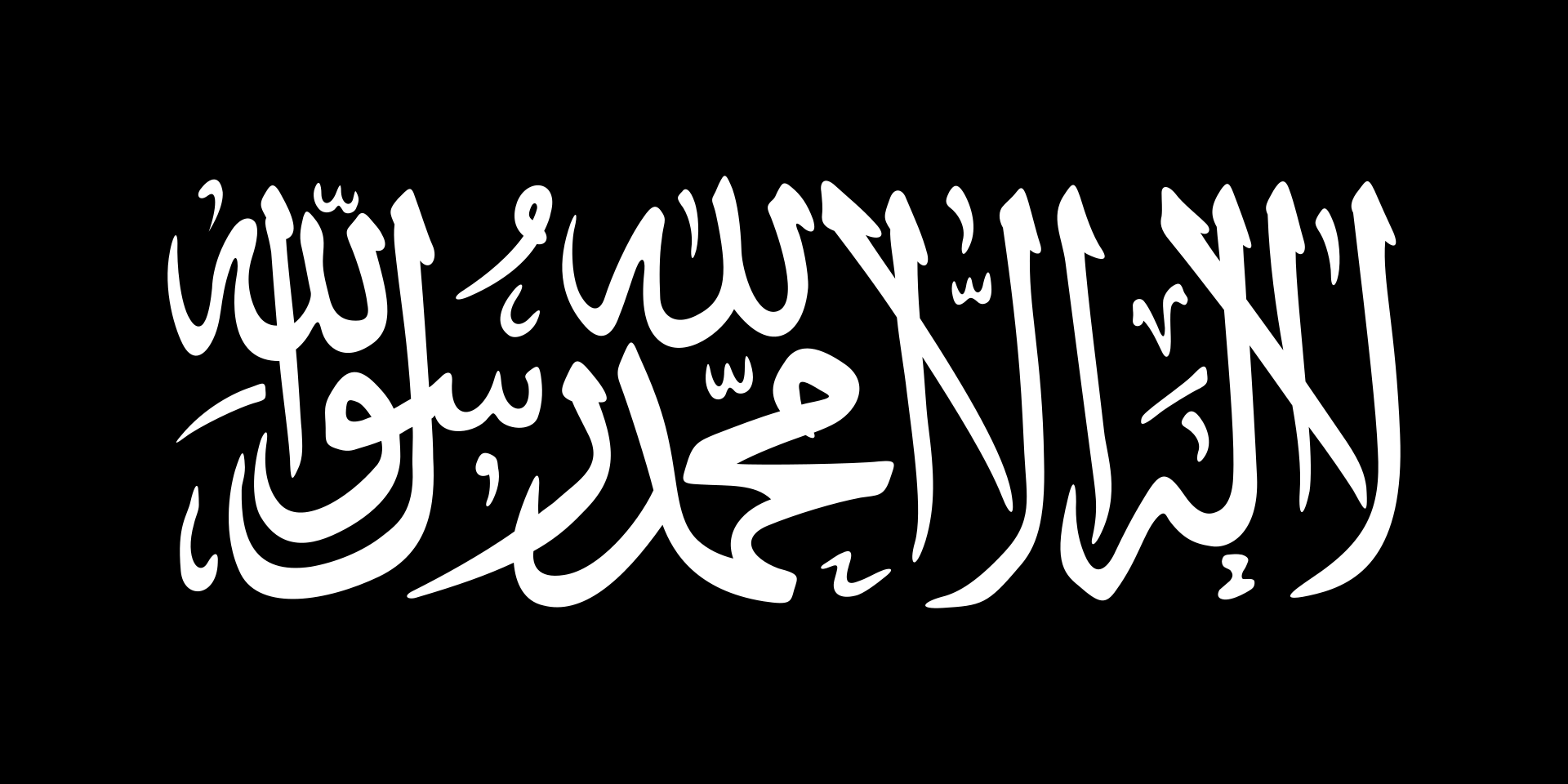

The flag commonly associated with ISIS—black with white Arabic script—has become an emblem of fear and extremism in Western media. Yet, the script itself holds a deeper meaning that transcends its current association. It features the Shahada, the Islamic declaration of faith:

“There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God.”

This statement is the foundation of Islamic monotheism and resonates with the core beliefs of Christianity, which also affirm the singularity of God.

Reclaiming the Message of the Flag

Vexillology, the study of flags, often reveals how symbols evolve over time. The jihadist flag is no exception. The core message of the Shahada should inspire reflection among all monotheists. Stripped of political and militant contexts, it is a unifying statement of faith that calls for solidarity among those who believe in one God.

Rather than allowing extremists to monopolize this symbol, monotheistic communities could find common ground in its message. This approach requires separating the core religious creed from its political misuse. By doing so, the flag’s deeper meaning—a testament to shared faith—can be reclaimed from its current associations.

A Call for Accountability and Consistency

The U.S.’s willingness to shift its stance on ISIS depending on geopolitical needs reflects broader inconsistencies in its foreign policy. These shifts not only undermine global trust but also perpetuate cycles of violence and instability. As the U.S. navigates its role on the world stage, a more consistent and ethically grounded approach is essential.

Moreover, reclaiming the deeper, unifying symbolism of the jihadist flag’s message offers an opportunity to counter extremist narratives. It allows for a reframing of discourse, emphasizing shared values rather than divisions.

Conclusion

The United States’ ever-changing relationship with ISIS in Syria underscores the duplicity inherent in its foreign policy. This duplicity, tied to pragmatic short-term goals, carries long-term consequences that often deepen global instability. Simultaneously, the jihadist flag—a symbol currently monopolized by extremism—has the potential to be reframed as a testament to monotheistic unity. By examining these dual narratives, we are reminded of the importance of ethical consistency in policy and the power of reclaiming symbols for a more constructive dialogue.