Your cart is currently empty!

The Grand Union Flag: A Vexillological Reflection on Ambiguity and Transition

The Meaning of a Flag Lies in Its Uncertainty.

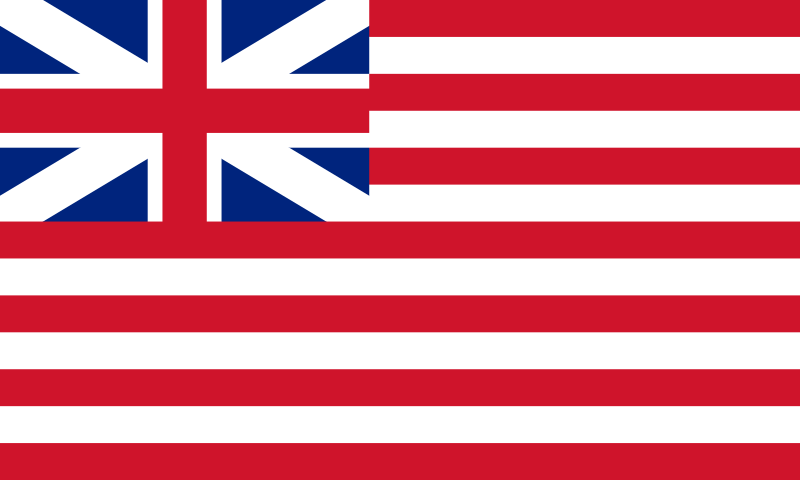

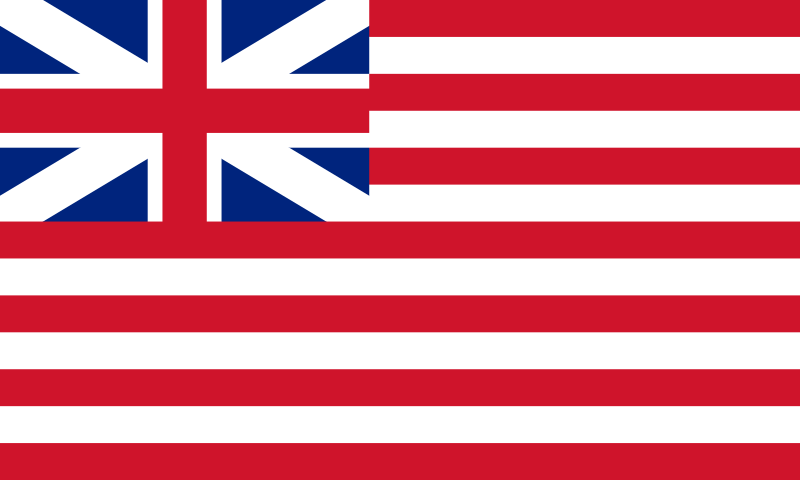

The Grand Union Flag occupies a strange and transitional space in the vexillological record. Sometimes called the Continental Colors or the Congress Flag, it is often credited as the first national flag of the United States, though it predates the Declaration of Independence and does not reflect the full rupture with British sovereignty. First raised on January 1, 1776, by General George Washington at Prospect Hill near Boston, the flag marked the beginning of a new phase in the American Revolutionary conflict. But what it actually meant—then or now—remains deeply ambiguous, revealing the inherent instability and subjectivity of all flag symbolism.

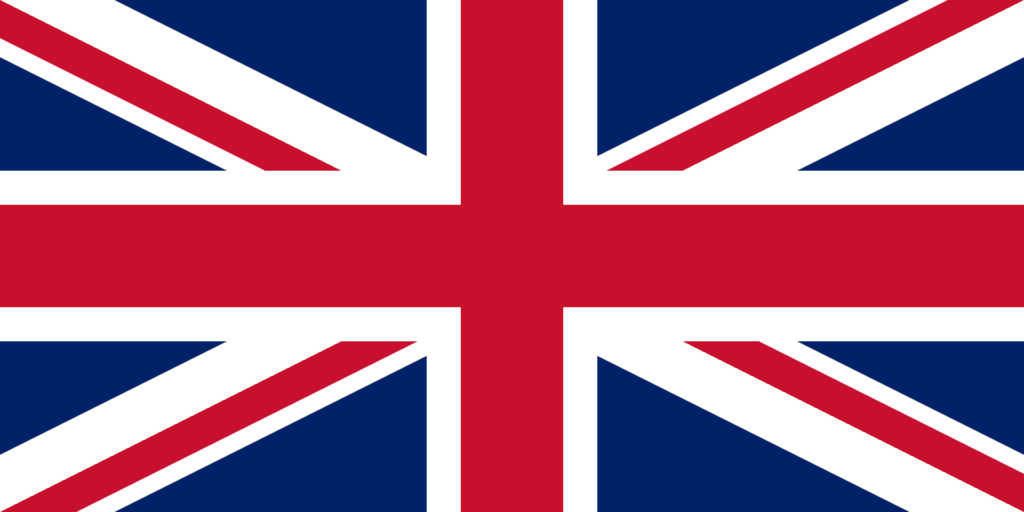

The flag itself consisted of thirteen alternating red and white stripes, representing the thirteen colonies, with the British Union Jack occupying the canton. This combination presented a dual message: on one hand, the stripes clearly signaled unity among the rebellious colonies; on the other, the Union Jack still connected the banner to the British Empire, visually aligning the colonies with the very power they were fighting against.

Such a contradiction is not unusual in vexillology. Flags, despite their visual clarity, often carry multiple meanings at once—some intended, others accidental, and many imposed by observers rather than bearers. The Grand Union Flag is a prime example of this phenomenon. For the Continental Army, raising the flag may have symbolized both defiance and continuity. For British observers stationed in Boston at the time, it was seen by some as a sign of surrender or reconciliation, given the presence of the Union Jack. This divergence in interpretation underscores the vexillological principle that flags are not static in their meaning; they are fluid symbols whose interpretations are shaped as much by context as by design.

The Grand Union Flag’s ambiguity reflects the uncertain political status of the colonies in early 1776. Full independence had not yet been declared, and many leaders in the Continental Congress still hoped for a negotiated settlement. Washington’s army was being reorganized into a more disciplined force, and the flag marked the formal beginning of that transformation. Yet it did not declare a new nation—it suggested a coalition of British subjects asserting their rights under the Crown.

This gap between design and interpretation is a common problem in vexillology. Flags are often created with a specific purpose or message in mind, but their meaning in public consciousness quickly diverges. They can be seen as declarations of war or peace, of solidarity or subjugation, depending on who views them and under what circumstances. The same flag can inspire one crowd and provoke another. The Grand Union Flag, as much as any banner in history, demonstrates this instability.

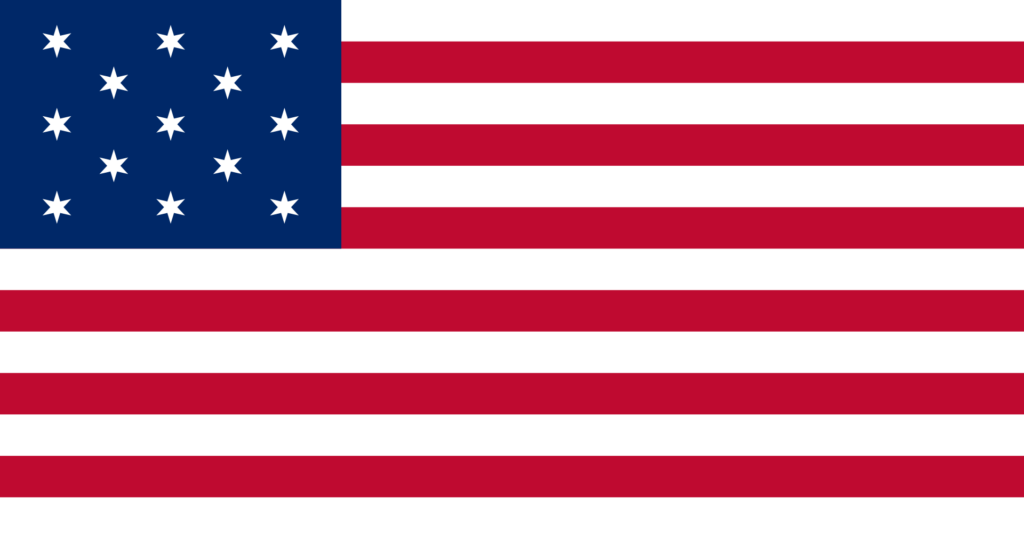

Following the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the Union Jack in the canton became politically and symbolically inappropriate. By mid-1777, the Continental Congress resolved to replace it with a new design: thirteen white stars on a blue field, representing a new constellation. The stars and stripes moved from ambiguity to assertion—from a flag of negotiation to a flag of nationhood. The Grand Union Flag, therefore, became obsolete, not because it failed as a design, but because it no longer matched the message the revolutionaries intended to send.

In this transition lies the core lesson for vexillology: flags do not speak for themselves. They speak through interpretation, through use, through time, and through the shifting sands of politics and memory. The Grand Union Flag is not just a historical artifact. It is a study in how meaning is never fixed, and how a flag’s message can be transformed, obscured, or reversed entirely depending on who sees it, who flies it, and when.

It is tempting to believe that a flag carries inherent meaning. But in reality, a flag is always a question.

The Grand Union Flag asked a question in 1776: are we still British, or something else? That it never answered clearly is not a flaw—it is its legacy.